News

Don’t hang your retirement dream on downsizing your property

The government is thought to be preparing financial incentives to nudge older people into smaller homes.

If you ask people how they plan on paying for their retirement, a common response is that “property is my pension”.

This could mean a buy-to-let that can be sold or milked for rent, but often boils down to a vague plan to use equity tied up in their home, which has risen dramatically in value over the years.

‘Downsizing’ is often the preferred route, and it has a neat logic to it. The family pile has served its primary purpose as a home to raise the kids, who have now grown and flown the nest. By selling a four or five bedroom house, for example, and buying a two or three bedroom replacement, you’re surely bound to be left with a handy windfall, as well as a less expensive property to maintain.

Another variation might be to swap a prime location in the commuter belt, say, for something more remote, on the basis that the daily schlep to work is now over.

‘Realities of downsizing fail to live up to day dream’

Such plans will undoubtedly work for some, but many others will find the realities of downsizing fail to live up to the day dream. Primarily, the promised windfall is chipped away at through the attritional costs of moving home. Preparing the house for sale, stamp duty, estate agency fees, conveyancing – it adds up.

What’s more, the reality of what you can afford and still leave a decent chunk of cash on top may be underwhelming.

The most recent Land Registry house price data confirms that the deferential between the price of the average detached house in England (£355,920) and the price of the average flat or maisonette (£221,917) is £134,003.

You won’t, however, walk away with all of that. Subtract the 1.8% of the selling price that Which? says is the typical estate agent fee, and the windfall shrinks to £127,596.

Then there’s stamp duty on the new flat (£1,938), conveyancing fees (approx. £1,000), structural survey and other checks (approx. £500) and miscellaneous moving costs (approx. £500). All this brings your proceeds down to £123,658.

If that money is to help fund retirement, then it’s prudent to plan on making it last for 30 years at least, assuming retirement starts age 65. This money could be invested with sums pulled down as income. A long-standing rule of thumb has been that 4% represents a safe level of withdrawal if you want your money to last 30 years, which is equivalent to £4,946 a year – and bear in mind this is increasingly seen as a rather optimistic rate for the UK.

Some might look at that figure and see the extra income as crucial to their standard of living. Others will regard it an insufficient reward for a less spacious or less convenient place to live.

And it’s important to remember that this example uses properties that occupy a comparable relative position in the housing market – the average detached house replaced by the average flat or maisonette. Whether this is really what potential downsizers have in mind is an open question.

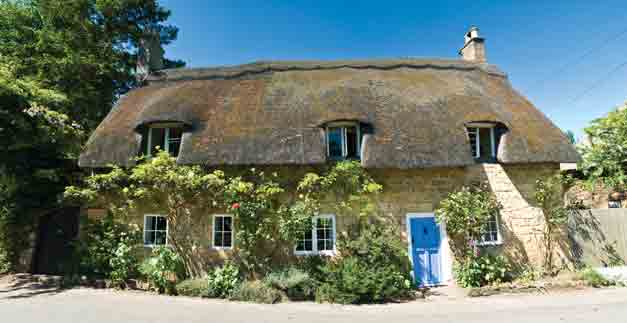

I suspect that their real dream is to trade their existing home for something that, while smaller, is more desirable in other ways. It’s in a beautiful location, it’s hundreds of years old or kitted out with dream kitchen and bathroom.

The reality is that, if freeing up cash really is the aim, then a bog-standard detached house will have to be replaced by a bog-standard flat, and that’s not exactly the downsizing dream.

‘We have good reason to promote downsizing’

All this is perhaps why the government is reportedly looking at ways to sweeten the deal. The housing White Paper due this month is rumoured to contain financial incentives for older people to downsize, perhaps through the stamp duty system.

That might be seen as another sop to older people, but we all have good reason to want to promote downsizing. The housing shortage helps very few people and one way to alleviate it is by making better use of the houses we do have.

It’s not the first we’ve heard of such measures. A Lib Dem peer, Lord Newby, two years ago suggested that more than half of them were rattling around houses with at least one spare room, and that they should be given a financial incentive to move.

He found himself fending off angry pensioners at the time, but similar measures may not meet with as much opposition now. The housing shortage has worsened since then and there’s greater attention on it. But what hasn’t changed is the paucity of suitable properties that older people would like to downsize into.

Other countries do a better job. Two years ago I visited Sweden to report on its rental property market. There were systemic differences to the UK market – more tightly regulated rents, primarily – but more important seemed to be the cultural differences.

Swedes do not share our obsession with home ownership and renting is regarded as a viable option for people up and down the income ladder. Business owners were just as likely to rent their home as their workers were.

The housing stock is also very different. In Trollhättan, the small town I visited, the centre was full of smart apartment blocks. These, we were told more than once, were the preferred option for many retired people who no longer needed a large family home. And why not? Apartments were spacious and housed in well-maintained buildings with all the amenities of town close by.

Contrast with UK urban centres, full of small flats with small rooms, subdivided from once larger houses and with poor accessibility, and it’s not hard to understand why British pensioners are less keen. In fact, I suspect that the idea of moving back into town would horrify most of them.

Downsizing may well be part of how we collectively cope with the challenges of paying for longer retirements in the future, but without more desirable destination properties at prices that leave the financial windfall intact, the reality may fail to match the dream.

Ed Monk is associate director for personal investing at Fidelity International