Household Bills

It’s not RIP for RPI – yet

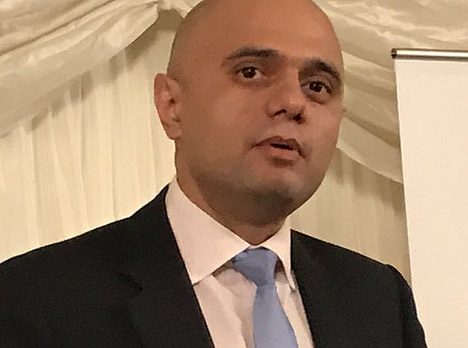

Chancellor Sajid Javid has refused to act on recommendations to change the Retail Price Index (RPI) – for now.

The government will keep using what is widely regarded as a flawed inflation statistic to calculate price rises for rail fares, student loan interest rates, and duty charged on cigarettes, alcohol and flights.

Javid made the announcement in a letter to UK Statistics Authority chief David Norgrove, who had urged the government to stop using or reform RPI.

Norgrove had described RPI as “not a good measure of inflation” and had written to Javid’s predecessor Philip Hammond in March calling for a rethink after a critical House of Lords committee report said RPI created “winners and losers.”

In his response, Javid said he recognised there were “flaws” in RPI but ditching RPI “would potentially be highly disruptive” and “damaging to the economy”.

He cited the government’s focus on Brexit as another reason not to scrap RPI at the present time.

Javid said he was “unable to consent” to changes any earlier than 2025, but pledged a consultation from January 2020 and ruled out extending the use of RPI any further.

Emma-Lou Montgomery, associate director at Fidelity International, said: “It’s not RIP for RPI today unfortunately – not least for rail commuters who would no doubt like to see the measure, which is used to determine how much rail fares go up by each year, scrapped – but the government has today signalled that the way it’s calculated will be reviewed.

“The fact that RPI is used so widely to determine some of the major living costs we face as consumers and yet the Office for National Statistics is effectively saying it’s not fit for purpose, is concerning.”

Tom Selby, senior analyst at AJ Bell, accused the government of selective use of RPI.

“The government’s reticence to abandon RPI is likely in part driven by the fact it has been used as a money-making machine in recent years. For example, back in 2011 the government chose to switch the inflation measure used for public sector pension increases from RPI, which on average tends to be the higher of the measures, to CPI, saving the Treasury tens of billions of pounds in the process,” he said, “However, in the case of student loan repayments RPI has been retained, again to the benefit of the Exchequer. A cynic might spot a pattern of behaviour emerging when it comes to the selective use of RPI and CPI.”

If RPI is eventually scrapped, the government will have to figure out what to do about the existing stock of products and benefits where the inflation measure is used.

Some private sector defined benefit pension schemes have RPI-linked increases in their scheme rules, while millions of people have bought annuities which rise in line with RPI.

Investors who have purchased index-linked government gilts from the Bank of England also see the value of their coupon or yield increase in line with RPI.

“It is far from clear what would happen to these savers and investors in the event RPI is ditched altogether. Any move to rip up existing contracts would inevitably end up in a messy legal challenge,” said Selby, “As a result it may be that, even if RPI is ditched officially, the ONS will need to continue producing a notional figure in order to ensure those with RPI-linked products are not adversely affected.”

The problem with RPI

RPI was introduced in 1947 and measures the changing prices of a basket of goods and services, including mortgage interest payments.

The Consumer Prices Index (CPI) was introduced in 2003 and Consumer Prices Index including Housing (CPIH) in 2013. The UK Statistics Authority stripped RPI of its official status in 2013 but continues to publish its data each month. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) adopted CPIH as its official gauge of inflation in March 2017.

RPI is usually higher than CPIH due to the different formulas used and how housing costs are incorporated in the basket of goods and services. RPI uses a combination of mortgage interest payments and house prices rather than the costs associated with running a household, while CPIH evaluates housing costs.